If you haven’t heard the news already, there’s a little bit of advice for theatre singers that’s been going around for a long time.

It has to do with the sinuses in your face, and folks who taught bel canto singers back in the day often used these mysterious skull caves as guide posts for singers to know they were making the right kinds of acoustically amplified sounds.

Versions of this legend have been passed down through oral tradition and may take on the form of phrases, such as “get it forward” or “use your mask,” or you may even have a visual of a very well-meaning voice teacher pointing on either side of their nose, and telling you to aim your voice there like a laser beam.

In my experience, all of this has been the opposite of helpful.

And I can tell you why real real quick.

First of all, nobody can hear what’s going on in your mask except for you. The only thing folks hear is what vibrates through your mouth and through your nose.

You might not even have the self perception to feel the resonance there, and that’s okay.

The second reason I never think this way or encourage singers I work with to think this way is because the vast majority of your resonance happens in a little place that I’d love to talk about.

That place is your pharynx.

If you snort, let your uvula flop back like your sawing logs at 3 AM (my wife reports I am expert at this these days, sorry sweetie) you’ll feel the spot.

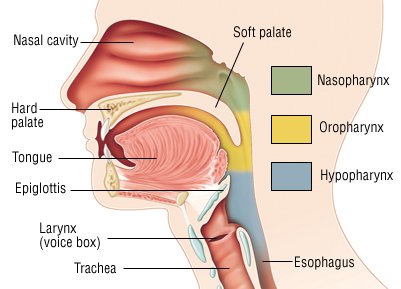

? In the above pic, you’ll see the blue, yellow and green portions — those are where your prime resonant money’s at.

Makes sense, right? They’re directly north of your vocal folds.

Your folds vibrate, and then all that vibration gets bounced around and amplified right there in the recital hall of your vocal tract.

Feeling resonance in your mask is an EFFECT, and what you’re feeling is nanoseconds past tense. The vibrations you’re feeling there are the result of what just came through your folds and pharynx.

In my experience, when I’ve tried to aim for the front, sing into my mask, or hit any kind of back row through a lot of forward resonance, my body recruits all kinds of muscles to direct this feeling to this spot.

And this makes the pharynx muscles do the only things they can — constrict.

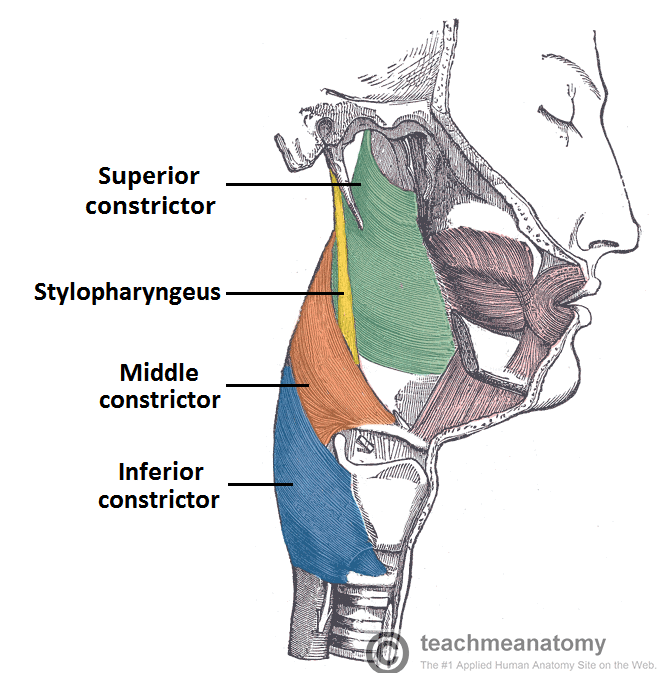

Lookit: (image courtesy of Teach Me Anatomy)

The green, orange, and blue muscle groups — they swallow for you hundreds of times a day. And the only thing they can do is get smaller.

To sing well, this mischief has to be managed. The softer and meltier these muscles are, the more room the recital hall (your pharynx) has to bounce sound waves around and amplify them.

If they’re squeezing just a little trying to laser beam your sound forward, well, you’re going to get a real samey, monochrome, bright metallic sound that honestly musical theatre gets made fun of for.

And for good reason — it’s dopey, and folks are missing out on all the individual color that the rest of their singular vocal tract can paint those sound waves with as they travel through.

So, what DO I do?

I encourage a dual perception — a centered awareness of the resonance vibrating through your vocal tract while your communication attention goes to your scene partner.

Musical theatre performers have to manage multiple awareness all the time.

I’m Christine Daae, I’m me, there’s the conductor, the audience is full tonight, that bobby pin is in too tight, maybe I’ll offer Raoul a breath mint later, I should have warmed up better before this show, I could use a nap, watch the conductor.

I’m astounded when folks believe we can’t think about vocal technique and storytelling at the same time. We have to. Humans have to think about more than one thing on the regular.

Yes, I know all the recent studies on how you can’t really multitask, and yes, hand raised.

But are you trying to tell me that when you’re scrubbing your tub you can’t sing “Alone” by Heart at the same time?

See?

I mean, anybody who’s sung and danced simultaneously can tell you that technique and singing can happen at the same time. Or else you fall over.

So here’s what I want you to understand:

Your primary resonance happens in your pharynx.

Folks can only hear what vibrates through your mouth and your nose.

Therefore, let’s do things that help these two factors happen as freely and efficiently as they can.

You might feel like your forehead’s gonna buzz right off your head, but someone could make a very similar sound and feel none of that.

Here are the questions you can ask yourself in order to find the sweet spot for efficient resonance and honest communication.

What are you singing?

What’s the world of the show or the song? Ado Annie’s gonna sing differently from A Little Night Music’s Ann, and she’s gonna sing differently from Ana in Frozen.

You’re a theatre singer. You make thousands of different sounds.

Once you know that,

What kind of breath support are you using?

“If I Loved You” support is gonna be very different from “Take Me or Leave Me.”

(”If I Loved You” is gonna have floatier ribs and be generated from the lower transverse abs and obliques [appoggio], and Rent is gonna have more rib closure and engagement which produces compressed phonation —

think toddler wailing over their banana being peeled the wrong way, broken, or slightly bruised. Those ribs know how to engage with the focal folds.

Then get a sense of the emotional impulse you’re working with.

Ado Annie: “It ain’t so much a question of not knowing what to do….”

Ann: “Soon, I promise. Soon I won’t shy away.”

Ana: “For the first time in FOREVER!….”

Three very different needs to communicate. These emotional images will light up in different parts of the body, and they’ll move the voice in a different way. Pay attention to your body on this.

Then, notice how that affects the phonatory pattern of the voice —

What happens when you notice the emotional energy of surmising, “It ain’t so much a question of not knowing what to do.”?

And how’s that different from Ann singing, “Soon, I promise….”?

And Ana’s got a completely different set of circumstances going on.

Your folds are going to sing these three different characters in different ways.

Now, it’s time to notice what the voice is doing just north of you larynx — in your pharynx.

Meditate your attention right back to that spot where your uvula vibrates against the back pharyngeal wall when you snort.

That’s the spot where I want you to notice your vibratory energy flowing past like a stream.

How does Ado Annie’s stream move?

How about Ann?

And Ana?

Notice the differences in air speed and how you feel the vibrations. Does that feel different from what you normally do?

Do you still feel sensations up in the front of your face? For me, I never think about them anymore. I may just be used to them, but I just don’t focus there.

Then after that, how can you shape your articulators and the rest of the tract to help you the most?

The one tip I have for you on this is to let your tongue float into your mouth. You want your tongue to float high and close to your hard palate.

This does at least 3 things:

1, it gets your tongue out of your most resonant place, your pharynx.

2, it floats the root of the tongue off of the larynx, so this whole mechanism has freedom to move.

and 3. When the tongue floats high toward the hard palate, it creates a very helpful acoustic bottleneck that causes sound waves to bounce back into the pharynx and amplify even more.

Then, the dialect of these characters, their self concept, and the world of the show are going to affect your articulation choices. Your entire body energy based on who you believe you are is going to shape how your tongue, teeth, and soft palate, and pharynx all interact.

And that’s the flow of energy that you have actual immediate control over. You can witness that as the actor/storyteller while looking to see if your communication is landing with your scene partner.

You can, in fact, do more than one thing at a time within a given task.

I hope this takes the pressure off of you to think you have to target and aim vibrations in a certain spot on your face. Sometimes you may feel sympathetic resonance galore in all kinds of places in your skull. Other times, you won’t.

That doesn’t matter. What does matter is that you are making free, efficient sounds that come from a deep belief and empathy for who you are being, and the story you are courageous enough to live.

Again, what I want you to walk away with from this is —

Your primary resonance happens in your pharynx. Nobody can hear your mask.

You can indeed think about vocal technique and storytelling at the same time. In fact, I believe they serve each other.

Trying to aim your voice in a forward direction can sometimes recruit muscles that decrease efficiency and cause unwanted constriction.

Then, when you’re working on any kind of material, ask yourself:

What world am I in? What am I singing?

What kind of breath support does this call for? What’s my body’s identity here?

How does this affect my phonatory pattern? What kinds of sounds am I making?

And then what do the resonances happening in my pharynx feel like as they flow through?

and then,

How do your articulators, affected by your body’s ego identity as this character or in this style, sculpt this vibration when it flows through your mouth?

And sub note on this, and this is a whole other topic — let your tongue float high and fill a lot of the mouth. It gets out of your pharynx, frees your larynx, and creates a terrific acoustic environment.

All of these things you have direct agency over. You can stand in your energy column, share generously, and observe how your scene partners respond with openness, curiosity, and play.

Practice these things, and reach out if you have questions at dan@dancallaway.com. Or click on “work with me” to find out how you can, well, work with me.

I’m all about getting you simple tools that make sense and work fast so that you can tell the stories you want to with joy, freedom and love, feel confident and excited at auditions, and contribute beautiful and satisfying work in whatever room you collaborate.

Because remember there is objectively, empirically, and scientifically only one you, and folks need to hear the story only you can sing. Now go sing. Bye. ?